KISS: Keep It Short and Simple

We are moving from a world where computing power was scarce to a place where it now is almost limitless, and where the true scarce commodity is increasingly human attention – Satya Nadella

A painfully accurate quote by the CEO of one of the largest software companies out there, research has indeed discovered that the average human attention span has dropped from 12 seconds in 2000 to a mere 8.25 seconds in 2015 [1]. Yep, that’s 0.75 seconds lower than that of a goldfish. Studies also show that the average reading speed for humans is roughly 240 WPM (Words per Minute) for the English language [2]. Of course, the results vary for different languages, but it gives us an idea of the approximate WPM we can read. Multiply that by the average attention span and you’ll get the number of words a person would probably read before scrolling away from the text. That number comes out to be about 33. So, you’re very likely to have lost your reader’s attention by the 40th word or so; just like I have lost yours, right about now (or have I?). In such a time where people are unlikely to read long texts, the KISS principle becomes our only hope to convey our message in 40 words or less. Enter, Automatic Text Summarization.

In my final year of college, we are supposed to work on a project for 2 semesters, preferably trying to solve a real world problem. And what better a problem to solve than that of communicating with fellow humans quickly and effectively. We, a group of 4, decided to take up a project on Text Summarization, a subfield of Natural Language Processing.

Introduction

A summary can defined as “a text that is produced from one or more texts, that conveys important information in the original text(s), and that is no longer than half of the original text(s) and usually significantly less than that”. Automatic text summarization is the process of extracting such a summary from given document(s).

Summarization can be categorised broadly as either extractive or abstractive. Extractive summaries carry the information taken from the original keywords, phrases or sentences present in the original document. Abstractive summarization involves the creation of novel sentences that highlight main ideas of the original document. Although it is obvious that human generated summaries are typically abstractive, majority of the summarization research is on extractive summarization. It is important to note that extractive summarization systems give results better than abstractive summarization systems. This is primarily due the inherent problems in abstractive summarization, such as semantic representation, inference and natural language generation which are relatively harder compared to a data-driven approach such as sentence or keyword extraction. However, assignment and extraction of high quality keywords manually itself is an expensive and time-consuming task. For our project, we took what can be called, a hybrid approach. We divided our project into two segments, the first where would find the best technique to extract keywords from a given text. In the second, we would use those keywords to create abstractive summaries (we intend to use neural networks for natural language generation). There are various algorithms for automatic keywords extraction that have been developed to save time and effort. We selected and compared performance of three popular keyword extraction techniques. The competing algorithms are (drum rolls…) TextRank, LexRank and LSA (Latent Semantic Analysis).

TextRank

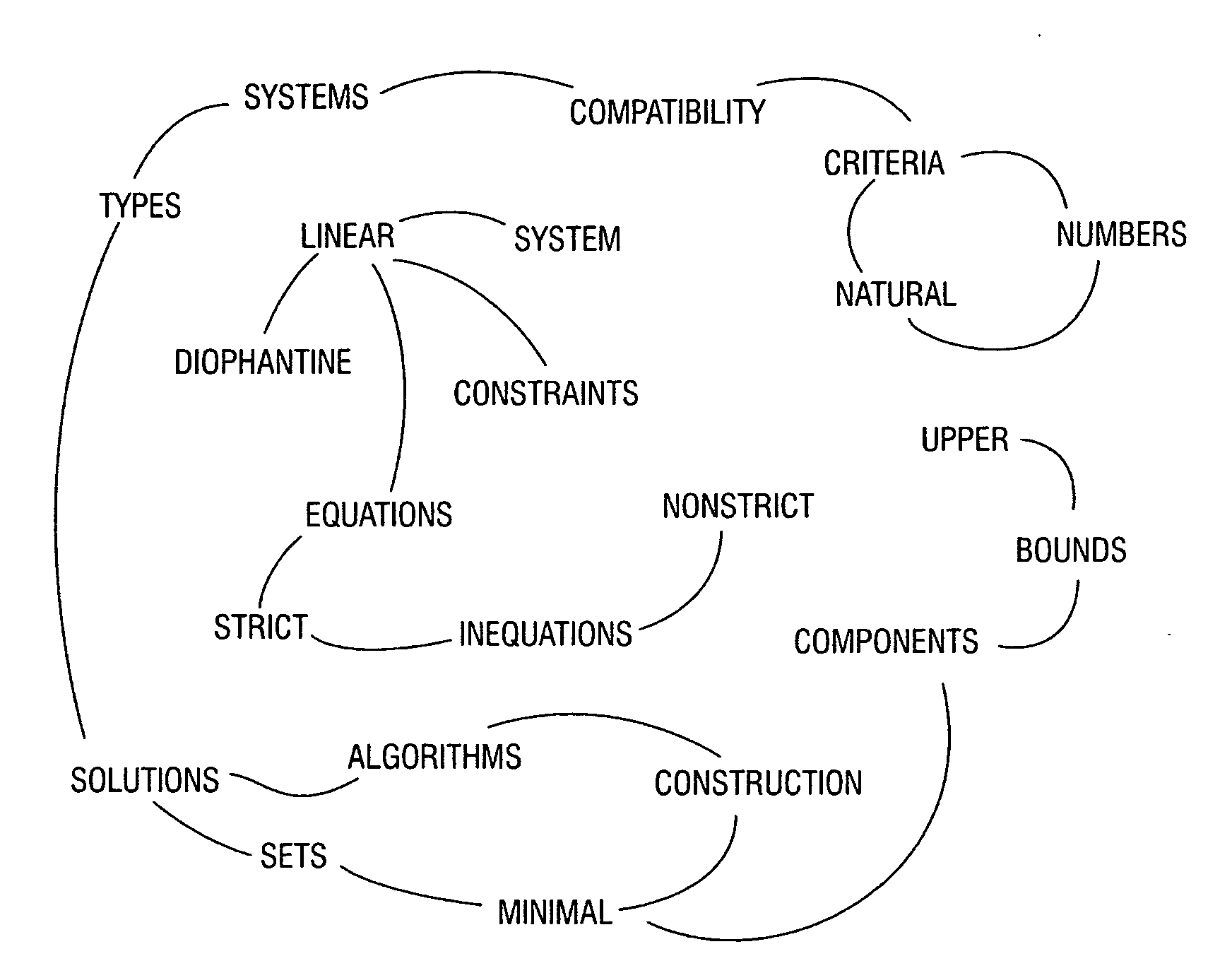

In their paper “TextRank: Bringing Order into Texts”, Rada Mihalcea and Paul Tarau [3] introduced TextRank as the first graph-based automated text summarization algorithm. TextRank algorithm is a simple application of PageRank algorithm. I won’t be going into the details of PageRank, TextRank or the equations involved in the computations of keyword weights for the fear of boring you to death (read the paper if you’re curious, it’s really nice). However, I can show you an image that might help you in getting an idea of what TextRank does. The following image is a graph that was created from a text on diophantine equations and inequations (no idea what that is, but it works).

The graph made above would then be subject to PageRank algorithm, which would eventually give us “numbers”, “inequations”, “linear”, “diophantine”, “upper”, “bounds”, “strict” as keywords. Neat!

The graph made above would then be subject to PageRank algorithm, which would eventually give us “numbers”, “inequations”, “linear”, “diophantine”, “upper”, “bounds”, “strict” as keywords. Neat!

LexRank

LexRank is another graph-based algorithm for automated text summarization, introduced by Güneş Erkan and Dragomir R. Radev [4] A cluster of documents can be viewed as a network of sentences that are related to each other. Some sentences are more similar to each other while some others may share only a little information with the rest of the sentences. Like TextRank, LexRank too uses the PageRank algorithm for extracting top keywords. The key difference between the algorithms is the weighting function used for assigning weights to the edges of the graph. While TextRank simply assumes all weights to be unit weights and computes ranks like a typical PageRank execution, LexRank uses degrees of similarity between words and phrases and computes the centrality of the sentences to assign weights. Again, I wouldn’t delve in the details of the algorithm’s governing equations, as it would easily make this post thrice as long as it already is. You may read research paper by Erkan and Radev cited above if interested.

LSA

Another popular and effective extractive summarization approach developed was the use of Latent Semantic Analysis for generating text summaries. Latent semantic analysis (LSA) is a technique in natural language processing, in particular distributional semantics, of analyzing relationships between a set of documents and the terms they contain by producing a set of concepts related to the documents and terms. LSA assumes that words that are close in meaning will occur in similar pieces of text. LSA found its use in text summarization when Josef Steinberger and Karel Ježek [5] demonstrated its effectiveness in extracting summaries keywords from textual data. They introduced a generic summarization technique which uses the latent semantic analysis technique to identify semantically important sentences.

The Experiment

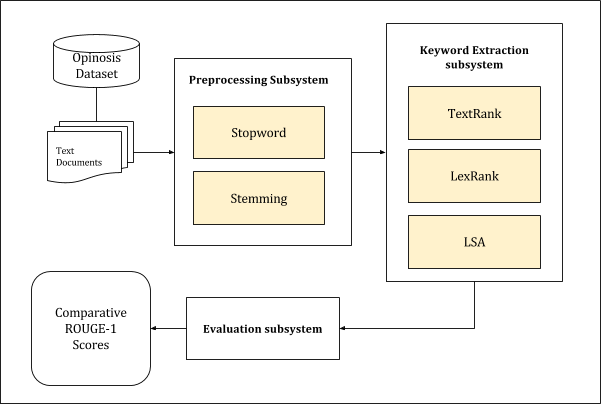

The first step for testing the effectiveness of these algorithms was selecting a dataset. The text should not be too specific about any particular genre of writing, nor be too generic to be summarized. After searching and comparing multiple datasets, we finalised the Opinosis Dataset for use in our project. The dataset contains 51 review articles, each about 100 sentences long, obtained from Tripadvisor, Edmunds.com and Amazon.com. The second salient feature of the dataset is that it comes with a set of 4 to 5 hand written summaries of each of these articles, courtesy of the authors of the dataset [6]. These summaries provide a perfect standard for comparing the relative performance of other algorithms. Without explaining all of the code, I’ll quicky run you through the setup, which looks like this:

The text is first preprocessed to strip out stopwords and stem the words (using Porter2 English Snowball Stemmer) for removing word derivatives. These steps are an important part of any natural language processing activity as they remove the unimportant words and allow the algorithm to focus on root words instead of different forms of the same word.

Having preprocessed the texts, we can now feed them to the algorithms implementations. The algorithms were implemented in Python using the sumy python library. Each of the algorithms then output a set of keywords which were stored for evaluation.

Evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the algorithms, we need a set of ‘gold’ keywords to compare the extracted keywords against. Here we used the human generated summaries to extract most frequent keywords. Only the keywords that appeared in more than half of the summaries were selected as ‘gold’ keywords for that particular article. We also measured the running time of each of the algorithms on the dataset.

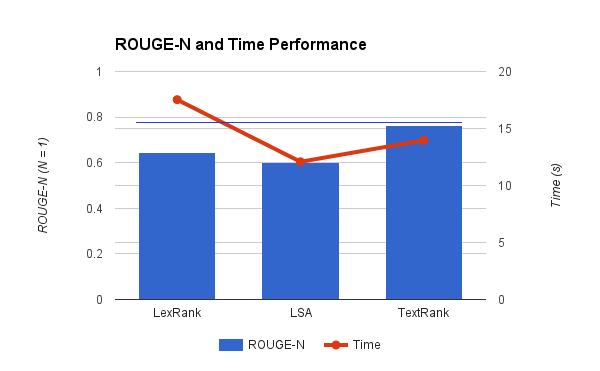

The evaluation metric we used was ROUGE-N metric from the ROUGE toolkit. Since we are considering only single-word keywords, N is set to unity. In essence, the ROUGE-1 parameters simply computes the ratio of number of keywords correctly indentified (i.e. keywords in sample that also occur in the gold set) to the total number of gold reference set keywords.

Results

The following image summarizes our results (summary of a summarization experiment, so meta…):

The blue horizontal line denotes the ROUGE-1 score of human generated summaries calculated by k-fold cross validatoin of each of the summa for every topic. As we can see, TextRank came out to be the winner. With a modest running time and a near-human ROUGE-1 score, TextRank was finally selected as our keyword extraction technique for the second phase of the project.

The code is available on Github.

That’s all for now folks. Expect another post on this subject once we’re done with second part too. We’ll try to make a research paper out of it, if our work is any good. Till then,

Live Long and Prosper